Prioritisation, as was once explained to me, is the ranking of perceived value of your various to-do list items.

At some level, value is therefore a deeply personal judgement that each of us uniquely defines. Art is stereotypically held up to make that case – beauty in the eye of the beholder and all that. How we choose to spend time is indicative of what we value in our identities. How we manage colleagues is indicative of what we perceive most valuable to our business’s objectives. And the list could go on.

It certainly follows then that we all grapple with agreeing on value; intrinsic, objective value. And so drivers of value become the tools for discourse in such discussions.

Investing is the search for value

Investing is the science of value determination, actively working to strip out the art: the subjective.

Value for investors is commonly understood in terms of businesses that provide benefits as they are held, used or developed. Assets that accrue worth, accountants might expand. Objective value, usually expressed as cashflow returned.

But this brings complexity as value therefore requires a view of the future. And value is definitively not price for that reason: what one person has sold or bought a business for reflects her view of the future (value of the company). Often this view will be significantly divergent from your own – and reality.

We anecdotally know this to be true. A car loses a chunk of its purchase price once you drive it off the lot – and yet the value of this vehicle to its owner remains far higher than its suddenly-discounted trade-in price. The value in use is higher than its replacement cost. In the hands of a driver, the value of the vehicle is disconnected from that of a seller.

Investors seek this underlying value disconnect: an opportunity to buy when sellers have a less clear vision or view of a company’s future, or are compete against their own other priorities (liquidity, fund lifecycle, reputation, relational breakdown) to attend to. Investing is the indeed the search for value of the underlying company.

Drivers of business value

To build a view of a company’s future, a first step should be moat recognition.

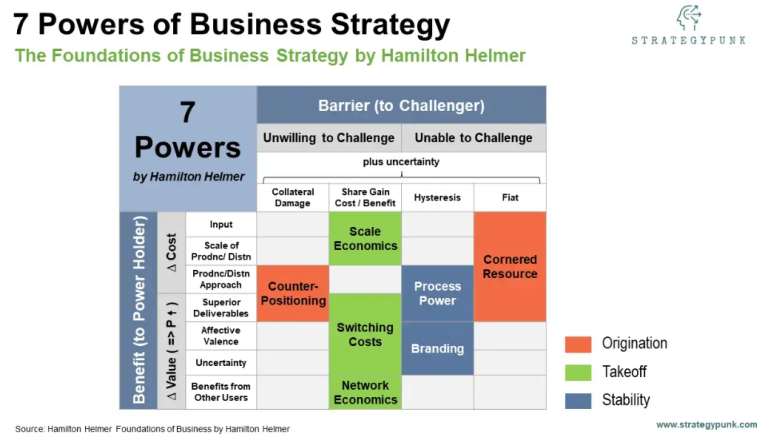

Moats are one of the very best descriptions for outsized value creation. They protect an above-average return form an otherwise competitive or understandable business model. Moats can be categorised in several ways – the most useful I believe is the 7 Powers Framework (Hamilton Helmer Foundations of Business by Hamilton Helmer).

Moats manifest in pricing power.

“The single most important decision in evaluating a business is pricing power. If you’ve got the power to raise prices without losing business to a competitor, you’ve got a very good business.” – Warren Buffett

Strong moats can be identified using the financial formula: ROIC > WACC. This should become an investor’s first thought when considering whether a business has value. And I’ll define value here for myself to be clear:

Value is the demonstrable capacity to continue generating outsized returns, relative to the operational risks of the plan.

ROIC vs. WACC

Return on invested capital (ROIC) is the after-tax operating profits of a business over its invested capital (NOPAT / TA – non-interest bearing CL – cash). It demonstrates what capital allocated to this business returns each year. WACC is the weighted average cost of capital. It should be close to the opportunity cost or hurdle rate for your investments.

ROIC > WACC can be generalised as a statement: the marginal benefit of a business activity must be higher than costs to engage in it. Historical performance is indicative of the ability of management to deliver on this over time, and here we must therefore assess what drives this value.

High ROIC indicates the presence of a moat. Which means that the business has been built with a Power harnessed.

Identifying moats

The 7 Powers framework was developed by Helmer and is an excellent tool to understand a company’s position. It is a framework to assess companies for greatness, not specific price today. And that’s what actually matters in the long run.

If the business earns 6% on capital over 40 years and you hold it for that 40 years, you’re not going to make much more than a 6% return- even if you originally buy it at huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns 18% on capital over 20 or 30 years, even if you pay an expensive looking price, you’ll end up with a fine result.” – Charlie Munger

Moats are what enable a business to earn 18%.

The diagram (thank you StrategyPunk) positions drivers of value into phases of business. Venture Capital investors ought to be looking at counter-positioned start-ups, or those with a cornered resource. PE houses focus on scale, network effects and stickiness. Larger companies outperform based on process and brand power.

Value and price

Many investors would readily accept a business earning a return of 18% p.a. into their portfolio. But paying a high price for such an asset diminishes excellent returns considerably.

Overpaying for a business however is a problem inversely correlated to length of holding period. The shorter the investment duration, the more diligence on pricing a company must take place.

This is the challenge of fixed-term funds. They must push for low entry prices and higher multiple exits, because a high proportion of their returns come from this re-rating. In the long run, as Munger points out, underlying business performance will carry the most weight.

Understanding what the seller most wants from the transaction helps remove this pressure. Sellers seldom articulate this clearly, and buyers are (understandably) not transparent about where they see future value.

Finding what it is that compels the seller is smart negotiating, and the shortcut to an acceptable buying price. This key part in the process is why advisory firms and boutique investment banks are paid to exist. They broker deals using this framework, and ensure that in return for their services, each party gains something of value.

To match value with an accepting buying price comes down to an understanding of the perceived value of a deal to the seller. Solve her biggest challenge – which in the VC and PE world is usually liquidity – and the price will provide real value to the buyer.

August 2023